zen reflections: letters on contemplative life

archive

- All

- Being Human

- Meditation

- Poetry

- Reflections

- WellBeing

- Zen

7 Tips to Help You Embark on a Journey of Self Discovery

March 30, 2024

Rolfing Structural Integration: The Ultimate Guide

March 30, 2024

What is a Spiritual Life Coach?

March 30, 2024

How to Realize Calm

January 18, 2023

How to Attend to the Present Each Day

November 15, 2022

How to Rewrite Your Destiny with Meditation

October 30, 2022

Audio

How to flourish through transitions

September 6, 2021

A Monk’s Life

July 5, 2021

What Makes Life Good

May 31, 2021

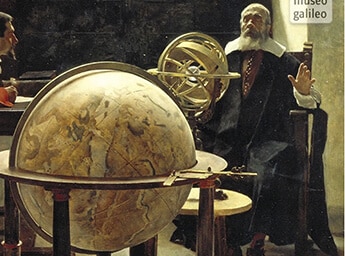

Zen and Goya’s Graphic Imagination

May 3, 2021

Renew Your Wind-Swept Spirit With Basho’s Poetry

April 5, 2021

How to Find Your Purpose in Life

February 18, 2021

How To Be Zen About Life

February 1, 2021

How To Find Yourself Again If You’re Feeling Lost

January 19, 2021

Finding Balance with Frantz Fanon

January 11, 2021

Setting Goals for the New Year: Make 2021 Your Best Yet

January 4, 2021

Is It Normal to Cry During Meditation?

December 15, 2020

Do I Need a Life Coach?

December 14, 2020

Disponibilité — Every Ideal Must Be Transcended

November 30, 2020

How To Clear Your Mind For Meditation: 6 Actionable Steps

November 17, 2020

Does Meditation Work for Everyone?

November 4, 2020

What We Love Loves Us

November 2, 2020

How Long Should You Meditate?

October 20, 2020

Can You Meditate Lying Down?

October 16, 2020

What Is the Goal of Meditation?

October 15, 2020

What Everybody Ought to Know About Healing in America

September 1, 2020

How to Make Peace With Change

August 3, 2020

How to Save Your Spirit in a Turbulent World

May 5, 2020

3 Meditations on Truth & Imagination

April 7, 2020

Healing Democracy

March 2, 2020

Who Am I – Practicing Self Inquiry

February 4, 2020

The Wonderful Matter of Trees

December 3, 2019

To Study the Way

November 4, 2019

Attending to Time

October 1, 2019

What is the Language of Autumn?

September 2, 2019

Summer Retreat

June 29, 2019

Rilke’s Temple: Rilke 4/4

June 24, 2019

Rilke’s Noble Lie: Rilke 3/4

June 17, 2019

How Rilke Might Steer You Wrong: Rilke 2/4

June 10, 2019

Treasures from a Poet About How to Live: Rilke 1/4

June 3, 2019

How to Make Your Phone a Good Thing

May 21, 2019

Is Meditation Selfish?

May 14, 2019

The Obstacle is the Way

May 7, 2019

Can You Guess the World’s Healthiest Country?

March 19, 2019

Ten Bad Traits Everyone Needs to Overcome

March 12, 2019

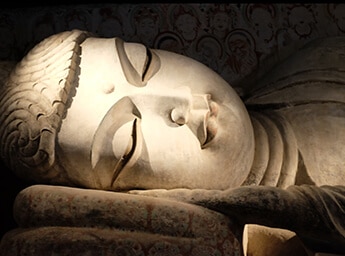

At Peace in the Nirvana Room

March 5, 2019

13 Facts any Intelligent Person Needs to Know About Happiness

December 11, 2018

You Are Already Meditating

December 6, 2018

Leonard Cohen and the Meaning of Life

November 29, 2018