At the time of this writing, my first real outing since Covid struck—other than to my temple in North Carolina—was yesterday. I ventured past my 14-block COVID-safety area to the Metropolitan Museum of Art double-masked and fully vaccinated to see “Goya’s Graphic Imagination,” which closes on May 2.

The outing was a disturbing experience for reasons I can’t quite put my finger on, but one I think we all share in this we’re-moving-out-of-the-pandemic-but-not time in which we seem to be living.

The Reality of Going Out

Many people are now vaccinated. And there is more freedom to move about and do things. But from what I saw and experienced yesterday, it strikes me that much more will be required to renew ourselves personally and as a society.

The world is changing in ways that even the most powerful people can’t deny. Socially, citizens don’t share commitments to policy, visions, or a sense of place. There are snippets of conversation in the air like, “Maybe I’ll move to San Francisco tomorrow,” “. . . waiting my instruction for this new set of circumstances,” “if people voluntarily opt to social distance . . .” Consumer habits show the biggest change since the Second World War, and interest in awards ceremonies such as the Oscars is lower than ever because people no longer believe in universal standards for art. Meanwhile in 2020, for the first time, Europe’s trade with China surpassed that of its trade with the U.S.

There are a number of disturbing observations I have to make because we can’t move past a thing we can’t name. One issue we all continue to experience is a sense of restriction. We can’t move about freely. You can’t walk up the Metropolitan Museum’s wide staircase through the front doors as you used to be able to do. Instead, you now have to file through a narrow lane to the right of the entrance in a line that forms outside the building. And social distance.

People are a little shlubby, too. They’re not exactly dressed in sweatpants, although some are, but there is a casual attitude of mind, a kind of sloppy comportment of self.

Goya’s Dark Primordial World

Goya (1746-1828) is a timely artist for the pandemic because his talent is to capture the dark, primordial movements of a society: especially the movements that cause a society, a civilization, and a person to erode. He pierces the veil of social custom and civil illusions in his drawings of hanging corpses, matadors, two-headed women, prisoners, and victims of the Spanish Inquisition in their dunce-caps and chains.

The demonic smiles of his dopey, maleficent giants frighten you the way you’re frightened by a stupid warden who might randomly arrest and torture you. There are drawings of witches eating children. And all of these illustrations are to depict to us the folly of human beings. They admonish us to pull our act together lest we and our society reach an irreversible state of decay.

Goya lived under a tyrant, and he also lived to see Spain’s resistance to Napoleon. He witnessed the effects of the Spanish Inquisition. Therefore, he was no stranger to the human appetite for power and domination, nor to human caprice. Goya saw humans as weak, susceptible to vice, and controlled by fleeting, sentimental pleasures.

His view of humans was that we generally live superficial, unprincipled, mindless, unreflective lives that easily crumble as soon as they are faced with the unimaginable tragedies that come from the unchecked depths of our psyches. His project was to show that we are surrounded by forces of darkness that soften and blind us to their ill effects until it’s too late to reverse the consequences of those effects.

And because of our complacency, we end up creating for ourselves a world of unimaginable suffering—the brutal world of hell.

What’s ‘Zen’ About Goya?

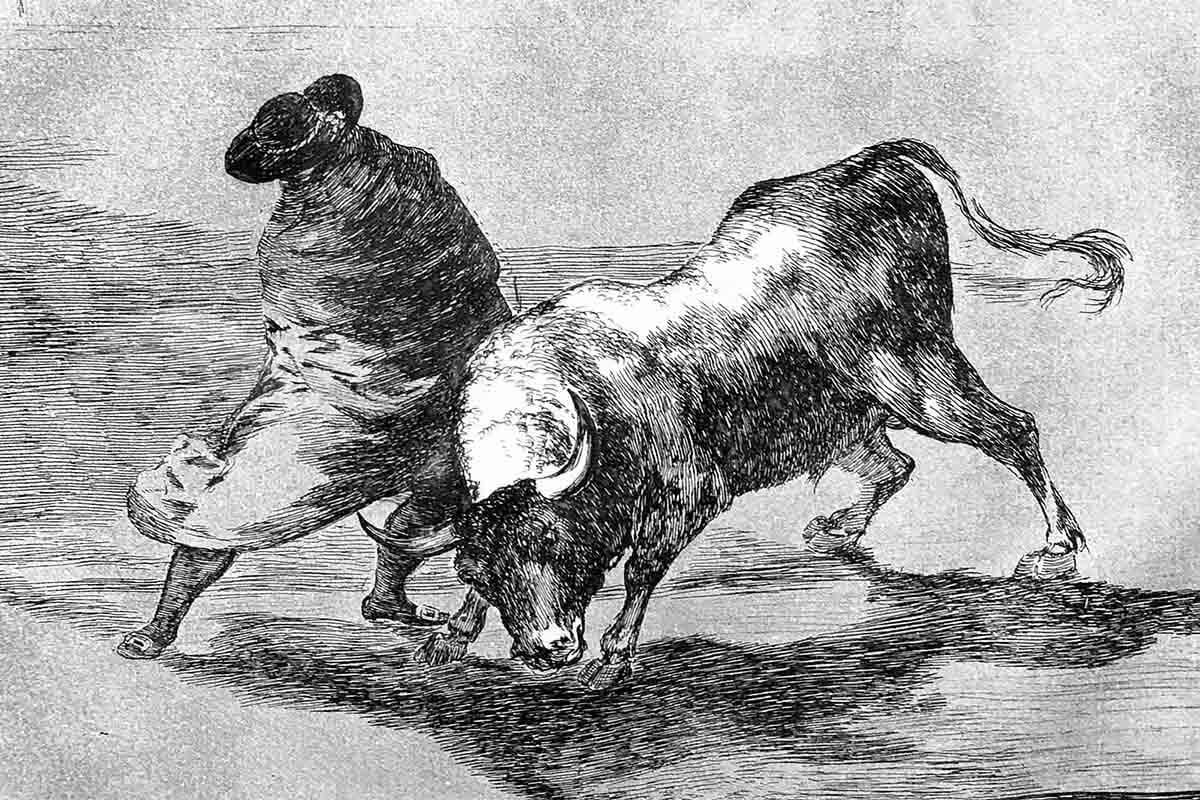

In the midst of Goya’s swirling darkness, one character that rises to the note of elegance and chivalry is the matador.

In many Eastern traditions, the bull or the elephant symbolizes the engine of human will and passion that has to be tamed by a training monk. In Tibetan Buddhism, the image is an elephant. In Zen, the image is an Ox. And in other traditions, the image is a snake.

For Goya, it’s the bull. And the matador is the chivalrous character who shows us how to overcome the forces of death. He is nimble, light, clever, daring, alert, cunning, artful, elegant, and audacious. To be sure, these are the qualities Goya admired—the characteristics he drew on to survive in his war-torn country. But in looking at Goya, there is another quality that comes through, viscerally more than the others: his more than empathic ability to feel another thing’s or person’s essence as his own.

Goya’s powerful renderings of gravity and motion, especially his ability to capture and convey the felt sense of movement between human beings, speak to his ability to know his subject from the inside out. Goya experiences the total subjectivity of what he renders, just as the bullfighter must know the heart of the bull to beat it.

The bullfighter must know what the body of the bull is going to do before the bull does. And to master the bull, the matador must become one with the bull. Goya clearly recognized that to master life, one must be able to become life—and also to be able to render it.

What struck me as odd at the museum yesterday, and afterward, walking through Central Park (redeemed by its plum blossoms but forsaken by its balding patches of grass), down 5th Avenue, returning to my apartment downtown, was the sense in which people seem to be floating through New York.

There is much less sense of a commitment to being here, to be in oneself, and, though I don’t think that anybody would quite put it this way—much less sense of a commitment to being in one’s life. It’s not that people aren’t visiting or enjoying coffee or drinks with their friends at Ralph’s café on 70-something-street and Madison Avenue. They are.

But much of people’s socializing feels disconnected. The creative class feels as though it’s gone, and, indeed, whole communities of artists have fled for Florida, upstate New York, or Mexico, small businesses are shuttered – and we’re losing more every day. Our old formulas for life aren’t working.

Of course, we need to connect with our friends. But something strikes me as having been eroded. The grass in the park is patchy. Garbage is piled on the curb. The lines for coffee are too long. Psychic, spiritual, energetic as well as physical movement—are restricted — even if, in theory, people can travel and move. There are new people on the neighborhood stoops. And they feel less gracious. Life on the street feels thin. And many people are gone—or thinking about leaving— perhaps never to come back.

Bringing Real Life Back to Ourselves

I’m not someone who thinks that New York City will disappear. There are already more signs of life. New York will come back in some new form. But it is going to take time. And it’ll be changed. What I learned yesterday is that to bring life back to the city, we have to bring life—real life—back to ourselves, and that to do so requires the difficult task of going back out into life as much as one can with all of the discombobulating discomfort required to do so.

I won’t go to the Met again for a while. I ventured too far too soon for my comfort. It was not the peaceful, easy, empty, “good-time-to-see-a-museum” experience I’d hoped for. Probably because it was Saturday. My visit was more like walking through a Goya illustration.

I was clear-eyed but sad at what I saw, sad for what’s happening to countries and people all over the world. But I’m wise enough to know that healing and self-renewal can only happen by acknowledging and going through this sadness. Reconnecting with ourselves in a genuine way reconnects us with the life that we need to connect with others.

New York, America, and the world will heal. And we will come out more thoughtful, empathetic, and kind toward others to the extent that we can be with ourselves and the vast array of feelings that have come up over the past year—feelings for which it’s sometimes hard to find words.

To think, feel, act, and speak is to live. This is how to self-renew. And to hold the intention to do so—the will and awareness—is to outsmart the bull, to dance and twinkle like a clear star to navigate the vessels of our lives. Buddhism teaches that it’s our nature to manifest a new self over and over again.

I’m sure that coming out of Covid, we’ll get better at renewing ourselves with others and with society. We can start with love, self-compassion, and wisdom that we grow, share and cultivate without losing our connection to what’s real—to the spirit that connects us all—from the inside out.