Reading Time: 8 minutes

Rilke has given us words to protect those parts of ourselves that help us stay open to fundamental questions about life. And should we lose this capacity, indeed, we would lose our capacity to be human . . .

Today I’m signing the closing papers for a construction loan to build a temple in the mountains of North Carolina. Once the papers are signed, the builder will have a year to build the 3,600 sq. ft. hermitage for Buddhist study. And then on Saturday I’ll head to Kyoto, Japan, to restore a temple there.

Both of these places are peaceful, in or at the foot of mountains, and nestled amid bushes and trees with stately views of their surroundings. Their purpose is to protect a space for anyone interested in studying Dharma.

One of the misleading tropes of American Buddhism, however, challenges my enterprise; it goes like this: If Buddha Nature is everywhere, why do we need a special place for it?

Master Kueishan

In one of his few recorded official lectures, Buddhist Master Kueishan (771-853) says:

The [Buddhist] trainee’s mind should be straight and should not be false. It should have no back and front, no deceiving and illusory mind. It’s good if he always sees and listens in an ordinary manner without having any crooked ways. And if he also doesn’t shut his eyes and plug his ears, and doesn’t develop attachments to anything. If there are not these bad recognitions, emotional views, and habitual thoughts, he can be like lucid autumn water, pure and not artificial. Being calm and undisturbed he can be called a trainee and also he can be the person having nothing the matter. (Zen Teacher Kueishan Lingyou’s recorded sayings in Tanjou)

By cultivating the ability to not be false, we cultivate the ability to be with others and all beings around us. And monasteries are the places for such cultivation—places, we could say, to polish our capacity for intimacy with life.

Advice to a Young Poet

This post is the last in a series of four articles on Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, in particular the first letter in which Rilke advises his correspondent, Mr. Kappus, that,

“Even if you found yourself in some prison, whose walls let in none of the world’s sounds—wouldn’t you still have your childhood, that jewel beyond all price, that treasure house of memories? Turn your attention to it. Try to raise up the sunken feelings of this enormous past; your personality will grow stronger, your solitude will expand and become a place where you can live in the twilight, where the noise of other people passes by, far in the distance.”

Reading this advice long ago gave me permission to explore the space of a vast inner world—a world that was always with me, mysteriously rich with material that deepened, and space that expanded, to the extent that I explored it.

Finding a Voice

In the space I encountered a voice—my guide through inner space. This voice awoke in me when I was twelve years old and read in Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha: “He [Siddhartha] would only strive after whatever the inward voice commanded him, not tarry anywhere but where the voice advised him . . . To obey no other external command, only the voice, to be prepared, that was necessary. Nothing else was necessary.”

Having established itself, this spiritual voice, a kind of close companion, guided me, for a time, as Dante’s Virgil, through various realms of hell, purgatory, and heaven, into my own divine comedy.

Eventually, I followed its call to a monastery, where, meditating as much as 24 hours in a day, an altogether new voice broke out, as if from a kind of ether that contained both the inside world and outside world as one—so that when a blue jay called on a hot August day, as night began to fall and cool the glittering granite boulders, and darken the sugar pines under which the meditation hall was nestled, and sandalwood incense filled the still, charged air—I could not tell if I were in the world in which the bird and sound and all these things appeared, or if that world and its things were in me. Consciousness became vast, absolute, utterly peaceful, and still. Time ceased and all became one. Though most likely an experience of abnormal psychology resulting from sleep deprivation, this experience was, for a time, what I came to know as solitude, as the innocence of childhood, far beyond childhood, with a power to heal and straighten out much that had been twisted in my mind.

Call to Intimacy

Reading Rilke now, I take his call to childhood and solitude as a call to intimacy, and openness, and to a direct, straightforward experience of ourselves—an intimation of the purity characteristic of our true nature and its capacity to heal and create. Indeed, solitude and childhood represent two aspects of one’s better mind: solitude—a functioning inner grace with capacity for revelation, insight, and healing; and childhood—the ability to see clearly, “like lucid autumn water,” the true and wondrous nature of the world around us. Rilke served me as a secular introduction to spiritual life. And to live from a truly spiritual mind, “straight and not false”—is, eventually, to replace one’s mind with Buddha’s mind; or, as my teacher has described it, to “develop and promote humanity as Buddha’s mind, as Buddha’s deed.”

Tied up by Shallow Concerns

Buddhism warns us against being tied up by shallow concerns such as established social custom, morality, culture, economy, politics, administration and laws—all of which make for artificial suffering. Because instead of relating to what is most important and fundamental in our lives, if we are concerned with such worldly matters, then we inevitably end up occupying ourselves with second-order concerns such as education, career, connections, income, mortgages, illness, medicine, honor, and position.

It’s not that we should ignore these elements of life—but they should not distract us from our primary concern, those issues which, as humans, we are destined to face—fundamental human problems cataloged by Buddhist master Seikan Hasegawa as, “aging, suffering illness, death, separation from loving affairs, meeting with hateful situations, being unable to obtain what we wish to have and having [attachments to] materials and mind.”

Human life doesn’t work properly if our human problems are not seen for what they are. And in Buddhism, even cancer, disease, and hardship are recognized as Buddha Nature. To provide a place to generate the capacity for the study, training, focus and composure that enables us to be with our difficulties and the difficulties of others, and to recognize them as Buddha Nature is, according to Buddhism, the true goal of all meaningful poetry, philosophy, spiritual thought, and practice—and the point of spiritual life.

Rilke’s Protective Words

In his letters and poems, Rilke has given us words to protect those parts of ourselves that help us stay open to fundamental questions about life. And should we lose this capacity, indeed, we would lose our capacity to be human. Similarly, places to nurse and cultivate such capacity are essential if we are to remain – and to protect the best parts of what it is to be – human. This is why I am building these temples. After all, without such activity, how can we hope to flourish and thrive as spiritual beings?

Summer Break

Soon, I will be going to Japan, and then I’ll be at work on a number of writing projects. So, this will be the last column before summer break. We’ll return in September. Meanwhile, I invite you to visit our blog. Feel free to read through the posts and comment on them. (You can comment as an anonymous guest if you like.) I promise to reply to your comments. Also, if you’re new to this series on Rilke, and you want to start from the beginning, you can do so here.

Until We Meet Again . . .

For now, I’ll leave you with the following:

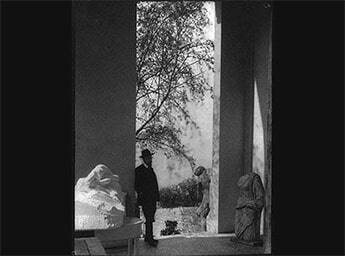

Reading through Rilke’s poems in preparation for this series of missives, I came across a poem he wrote while working with Rodin in Paris. In the poem, Rilke writes of a Buddha statue on one of Rodin’s properties. Rilke saw the sculpture through the window. He describes the scene in a letter to his wife on September 20, 1905 as follows:

“Soon after supper I retire, and am in my little house by 8:30 at the latest. Then I have in front of me the vast blossoming starry night, and below, in front of the window, the gravel walk goes up a little hill on which, in fanatic taciturnity, a statue of Buddha rests, disturbing, with silent discretion, the unutterable self-containedness of his gesture beneath all the skies of the day and night. C’est la centre du monde [He is the center of the world], I said to Rodin.”

And here is the poem:

BUDDHA IN GLORY

Center of all centers, core of cores,

almond self-enclosed and growing sweet—

all this universe, to the furthest stars

and beyond them, is your flesh, your fruit.Now you feel how nothing clings to you;

your vast shell reaches into endless space,

and there the rich, thick fluids rise and flow.

Illuminated in your infinite peace,a billion stars go spinning through the night,

blazing high above your head.

But in you is the presence that

will be, when all the stars are dead.

Revelations of Mind

May you find this summer the revelations of mind that sustain your power to heal—the core of all cores—by which you may live calm and undisturbed for the sake of the dear beings around you.